The heart is the driving force behind human life. It tirelessly propels blood throughout our body; beating an average of 2.5 billion times over the course of a person's life. It is surprising then, that given its vital importance, the notion of the heart as a muscle that pumps blood was not widely accepted until the 17th century.

The ancient Greeks were aware of the heart and blood vessels, and many theories about the function of the heart had been already considered by 300 BCE. In the History of Animals, Aristotle (384 - 322 BCE) rejected the commonly held notion that the brain was the source of the veins, instead he concluded that all blood vessels stemmed from the heart (2). He considered the heart as a type of container that served as a resting point for blood on its voyage between the aorta and the vena cava. In addition to his misunderstanding of the heart's purpose, Aristotle thought that there were only three cavities of the heart: the left atrium, left ventricle, and the right ventricle (2) - it is believed that Aristotle mistook the right atrium as being part of the vena cava (3). Herophilos (335 - 280 BCE) had differentiated between the arteries and veins by the thickness of their walls. He also determined that veins carried only blood, and not a mixture of blood and air (2).

The role of the heart put forth by Aristotle and Herophilos survived for almost 500 years, until the Roman physician, Galen (ca. 130 - 200 CE). Galen built upon Herophilos's theories to conclude that the arteries too, contained only blood. Galen also set straight the number of chambers in the heart, from three to four, for which he chastised Aristotle: "What wonder that Aristotle, among his many anatomical errors, thinks that the heart in large animals has three cavities?" (2). Galen discerned that the heart controls its own pulsations and he noted the muscular nature of the heart; however, he failed to make the connection that the heart functioned as a muscle to drive blood, instead he thought that it dilated to draw in blood (4). Like his predecessors, Galen thought that the venous and arterial systems were separate: the venous blood carried nutrients and originated in the liver; the arterial blood transmitted the "vital spirit" from the lungs to the rest of the body through the heart. Galen likened the heart to a furnace, providing heat for the body and as such, produced a sooty waste. The soot was cleansed by blood coming from the lungs, which mixed with venous blood through tiny pores in the septum between the left and right ventricles (2, 4).

Not much changed in the theory of the function of the heart until several independent observations were made 1000 - 1400 years later. The physician, Ibn Al-Nafis (1213 - 1288 CE), while working in Cairo, was the first person to publically renounce Galen's postulate that blood from the right ventricle mixed with blood from the left ventricle through the septum. The lack of pores between the ventricles led him to conclude that blood comingled in the lungs, and then returned to the left ventricle of the heart, making this the first rudimentary description of pulmonary circulation (2, 5).

A few centuries later, the anatomist, Andreas Vesalius (1514 - 1564 CE), criticized Galen's knowledge of anatomy. Although a great admirer of his, he corrected approximately 200 errors made by Galen, including noting that the septum did not contain pores (2). The first European to describe of pulmonary circulation was the Spanish-born theologian and physician, Michael Servetus (1511 - 1553 CE). Servetus published his conclusions (see quote) in a pamphlet entitled, The restoration of Christianity (1). In The restoration of Christianity, Servetus also criticized the Trinity, which led to the destruction of most of the copies of the manuscript and his ultimate burning at the stake (2, 6). Pulmonary circulation was again described by Servetus's contemporary, Realdo Colombo (ca. 1510 - 1559 CE). Colombo worked at the University of Padua as a dissectionist under Vesalius. Colombo again denied the presence of pores in the septum of the heart and defined the pulmonary circuit. It is likely, however, that Colombo knew of Servetus' work, but did not explicitly reference Servetus for fear of persecution by the Inquisition (6). Colombo also disagreed with Galen's idea that the heart functioned as a furnace producing fuliginous waste and he was the first person to state that the heart 'set the blood in motion' (2).

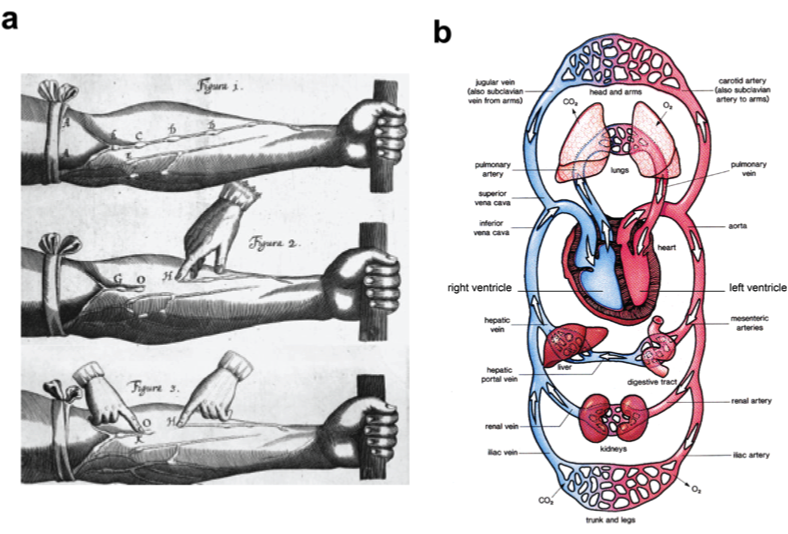

Hieronymus Fabricius (1537 - 1619 CE) also worked at the University of Padua and noted the presence of valves in veins, astonishingly not discovered until him! However, physicians would not be completely free of the shackles of Galenism until discoveries made by Fabricus's student, the English physician, William Harvey (1578 - 1657 CE). Harvey described the systemic circulation of blood, a notion he supported from the fact that the amount of blood far exceeds the quantity that could be made by the liver from food. Harvey also noted that all the valves in the veins point towards the main veins and heart, and therefore their function was to prevent the flow of blood away from the heart, towards the smaller veins. Instead of thinking of the heart as a way station or a dilator that draws blood into it, Harvey described the heart as a pump that drove blood around one large circuit of the body (2, 7).

The contemporary view of the heart and circulation has only slightly changed since Harvey's findings. Briefly, the heart drives blood through the pulmonary and systemic circuits. Blood freshly fuelled with oxygen at the lungs travels to the heart via the pulmonary veins into the left atrium, and on the left ventricle. The left ventricle is tasked with propelling blood throughout the entire body, starting at the aorta and spreading outward by a network of arteries. Following the transfer of nutrients and oxygen through capillaries, blood returns to the right side of the heart by the superior and inferior vena cava. It is then pumped from the right ventricle to the pulmonary arteries and on to the lungs, thereby completing its full circuit of the body (8).